Fast fashion: How airfreight shapes retail’s competitive edge

- By Nour Farid

- •

- 29 Apr, 2024

As fast and ultra-fast fashion

grows with the rise of Far Eastern brands such as Shein and Temu, so does the

pressure on the airfreight market. This puts into question the sustainability

of their e-commerce model given the competition for airfreight capacity and its

environmental implications.

Global supply chains have been

subject to several recent disruptions, most notably the COVID pandemic and hostilities

in the Red Sea. A lesser known but equally significant disruptor in the

airfreight sector is the rise of e-commerce. Major online e-commerce retailers

such as Shein and Temu largely depend on airfreight to transport parcels

directly from warehouses in Asia to customers in Europe and North America,

buying up short-term empty capacity at discounted rates. However, their growth

has increased demand for airfreight capacity at the same time as industries explore

alternative options to shipping through the Red Sea. The outcome is a rise in airfreight

costs from Asian hubs such as Guangzhou and Hong Kong due to capacity shortages.

Fast fashion

A certain business model has developed with the rise of ‘fast fashion’, a relatively recent phenomenon that gained traction in the late 1990s. Associated with affordable clothing that produces similar designs to luxury brands using lower quality materials and production methods, it allows customers to keep up with changing trends. It is often characterised by poor quality of clothing, unethical working conditions, and excess waste as items are only used a handful of times due to its poor quality and consumers’ desire to keep up with fast-changing trends.

This business model took shape as retailers started exporting production to countries with lower wages which made rapid product turnaround possible. This meant that, while new collections used to be released four times a year, clothing could now be produced at a much faster rate. ‘Ultra-fast fashion’ operates on an extreme version of the model, where stock is resupplied in a matter of days.

Coupled with faster production it ensures that items are available on shelves at the right time. To remain competitive, high-street brands have opted for the use of air freight; the transport mode that provides the fastest door-to-door delivery times from international manufacturers, likely to be located in Asia. Fast fashion retailers such as Zara and H&M aim to renew collections as frequently as every week to match the pace of fashion trends. In the case of ultra-fast fashion, retailers dynamically respond to customer demand by placing production orders only for products that perform well, to be transported using aircrafts to achieve short delivery windows and resupply stock in a few days.

E-commerce distribution models

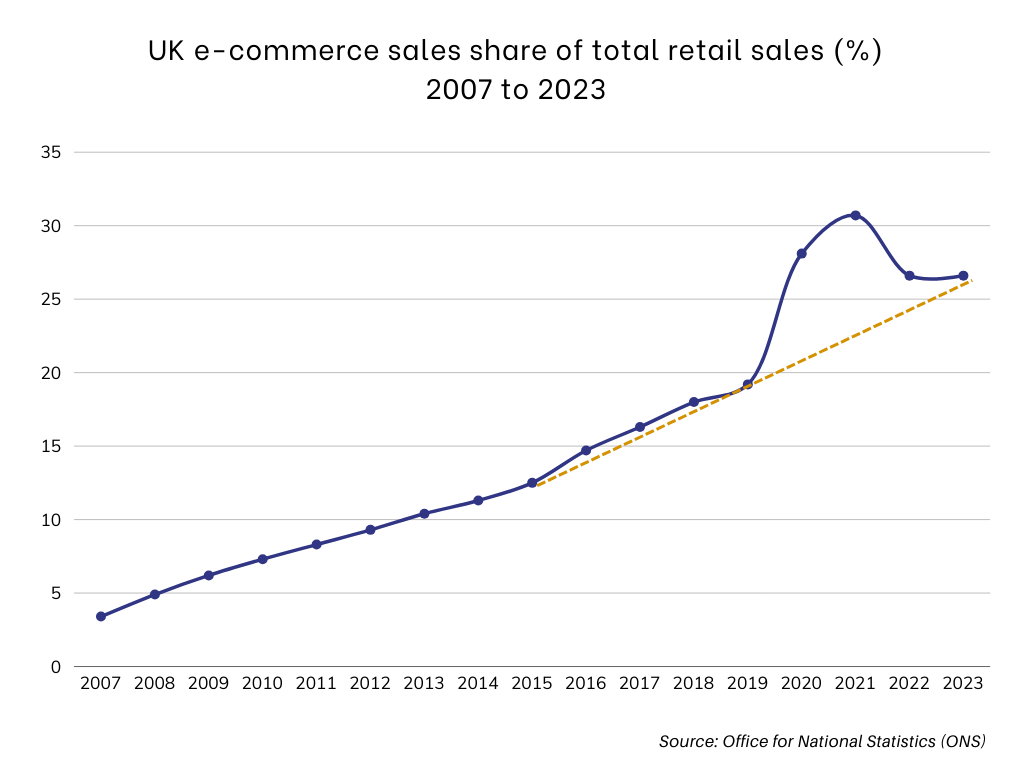

During the COVID pandemic, e-commerce experienced significant growth. Figure 1 shows that in the UK, the e-commerce shares of retail sales grew from 19% in 2019 to its highest of 31% in 2021 but have fallen back following the resumption of previous trading practices.

In the fashion industry, ultra-fast fashion retailers that operate only online such as Shein and ASOS were able to benefit from increased demand and ship parcels from their warehouses directly to consumers. This contrasts with the standard ‘logistics model’ used by e-commerce retailers which is based around customer fulfilment centres (CFCs). CFCs receive goods from multiple suppliers, principally via sea freight but also using airfreight for higher value and faster moving lines, where they are stored before delivery within the country and to customers in the surrounding region. Recently, their location has focused on mainland Europe; prominent examples include Next or Amazon. For instance, alongside its UK warehouses, Next operates a German hub that processes and packs online orders for 13 countries as well as handling European returns.

By contrast, online retailers such as Shein and Temu process items in their Fast East distribution centres and send them directly to customers in individually addressed packages. Despite operating warehouses in America, Europe, and the Middle East, most stock is in China where orders are split into sub-orders and shipped below the customs threshold where applicable. In the United States, a trade rule known as ‘de minimis’ exempts packages with a value under $800 from customs duties. In the UK, a similar rule is in place for parcels under £135. A report by the U.S. International Trade Commission found that de minimis imports account for 83% of all e-commerce imports in fiscal year 2022, increasing by 88% from 2018. Of the total de minimis imports from 2018 to 2021, approximately two-thirds were from China. These are shipped through the purchase of spare airfreight capacity at discounted rates to quickly deliver parcels to customers.

Environmental implications

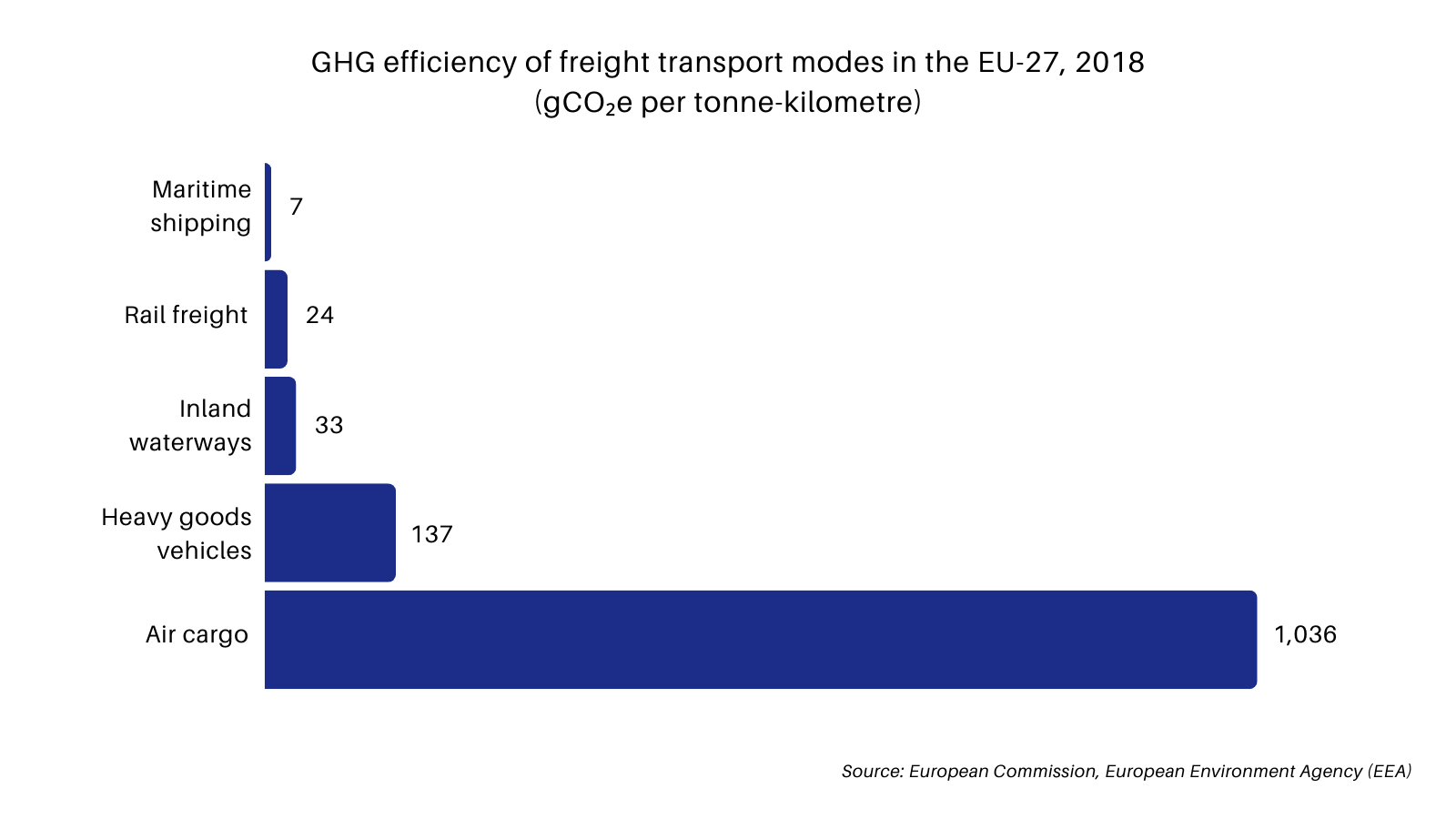

Increased use of airfreight inevitably raises environmental issues. As Figure 2 shows, air cargo is the most carbon-intensive mode of freight transport per tonne-kilometre.

Shein reported in 2022 that the growth of its production from the previous year led to a 52% increase in emissions which reached 9.17 million tonnes CO2e. It also announced it would begin implementing decarbonisation programs at the end of fiscal year 2022. It aims to be carbon neutral in its operations and facilities by 2030, which make up less than 1% of its total emissions. Emissions from its supply chain, where most of its emissions lie, are to be addressed by promoting renewable energy use and energy-efficient projects. It was recently reported to be expanding its existing U.S. facility in Indiana and opening a new warehouse in California, and is looking into increasing its volumes shipped using maritime freight. The aim is to ultimately reduce the cost of transport and reduce transport time by storing goods in its global network of warehouses.

Conclusion

The relative affordability of airfreight through the purchase of spare capacity has facilitated the rise of ultra-fast fashion. However, as major e-commerce retailers such as Shein and Temu continue to grow, the longevity of their supply and distribution model is likely to be questioned. Specifically, can there be long-term reliance on airfreight given the competition for capacity leading to upward pressure on rates? In addition, can the increased use of airfreight be justified given the significant GHG emissions emitted compared with other modes?

Expanding locations of regional warehouses to be closer to customers, in addition to switching transport away from airfreight, could suggest ultra-fast fashion retailers are moving towards a more standard logistics model. However, lead times are considered the key drivers of competitive advantage in the industry. Therefore, as long as demand for ultra-fast fashion remains, its distribution will have to find a balance between being timely, cost-efficient and environmentally sustainable.